Hurricanes frequently make landfall in the US, causing massive damage – both in terms of human lives and dollars. And yet, population and housing only seem to grow in hurricane-prone regions like the southeastern coasts of the US.

From June through November, the Atlantic becomes the center of attention for meteorologists as they watch for signs of trouble. What starts as a few scattered thunderstorms over Africa can evolve into immense, rotating storms, stretching over 900 miles wide and releasing energy equivalent to 200 times the world's electrical generating capacity in a single day.

When they make landfall, these storms are costly.

Globally, the United States ranks second behind the Philippines in annual economic losses from weather-related disasters (relative to GDP), with landfalling tropical cyclones being the leading cause of both weather-related economic damage and weather-related deaths in the country.

Costliest landfalling cyclones in the United States

Hurricane Katrina (2005, $200.0B)

Hurricane Harvey (2017, $158.8B)

Hurricane Ian (2022, $118.5B)

Hurricane Maria (2017, $114.3B)

Hurricane Sandy (2012, $88.5B)

Growth in population, housing, and wealth in coastal areas with frequent landfalling hurricanes

From 1970 to 2016, the Gulf Coast and Atlantic population grew by over 60 million. In the same period, 34 million new homes were constructed, representing 51% of the new housing in the United States.

It isn’t just people moving to these areas, but also money: Since 1995, Texas, Florida, and North Carolina have all had higher than average annual increases in GDP. Florida and Texas also boasted twelve of the top 20 fastest growing US counties from 2010 to 2016.

The numbers paint a clear picture: People love living in the coastal southeastern United States, and this is unlikely to change anytime soon.

Since 1980, tropical cyclones have caused over $1 trillion in damages and almost 7,000 deaths.

“Billion-dollar cyclones” are particularly damaging tropical cyclones that cause at least one billion dollars in damages. Each billion-dollar cyclone event costs the US an average of $22.8 billion.

The eastern states bear almost all the major economic damages from these storms. Since records began, due to the general movement of hurricanes from east to west, almost no hurricanes have made landfall in the western US. The exception is Hawaii, because of it’s location in the central Pacific, which has experienced a single billion-dollar cyclone since 1980: Hurricane Iniki in 1992.

Florida, with its exposed geography and coastlines, has suffered the greatest economic impact from cyclones out of all states, with damages exceeding $370 billion. Texas and Louisiana follow, each with over $200 billion in damages.

The climate is rapidly changing – but are landfalling hurricanes in the US more frequent than before?

The current scientific consensus is that there has been no significant increase in U.S. tropical cyclone landfall frequency since 1900. But the full answer to this question isn't so straightforward.

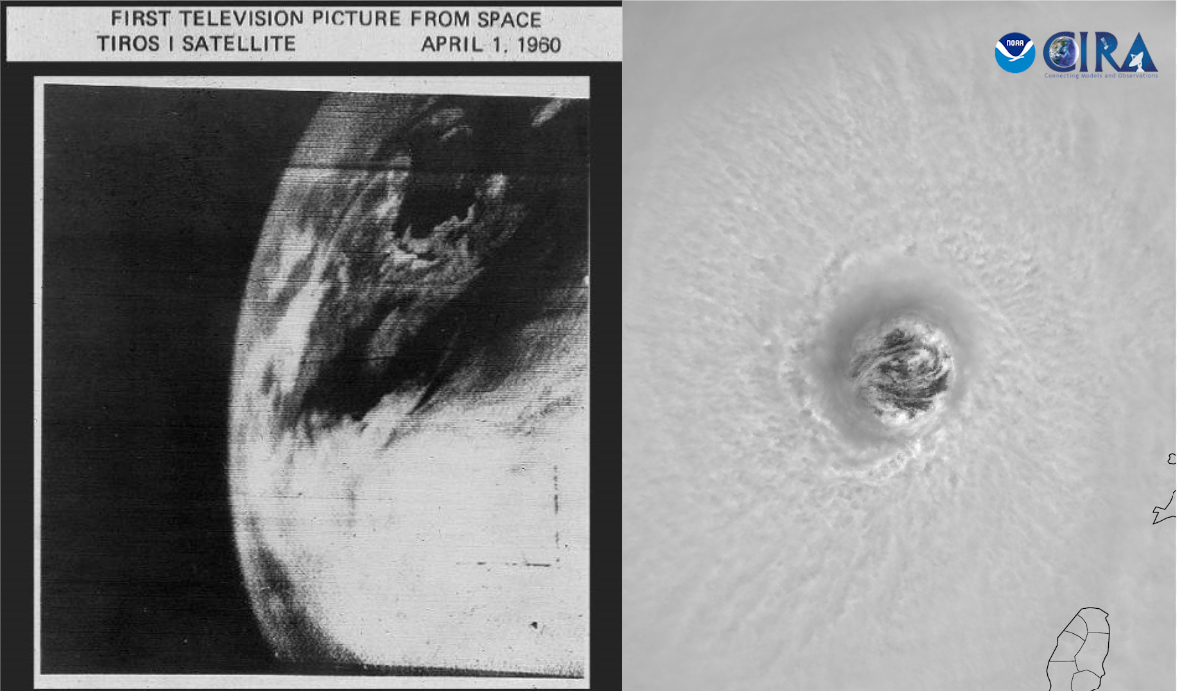

The observation and monitoring of hurricanes have changed significantly over the past 100 years. In the 1800s, hurricane observations were made only from land and from ships that encountered the storms. Aircraft and radar observations began in the 1940s, and the first weather satellite, TIROS-1, wasn’t launched until 1960.

Since then, the number of orbiting satellites and the quality of images and data have improved significantly, allowing us to capture high-resolution data in all basins. While Atlantic hurricane data may appear to show increased storm activity, this rise is mostly due to advancements in monitoring technology, like satellites.

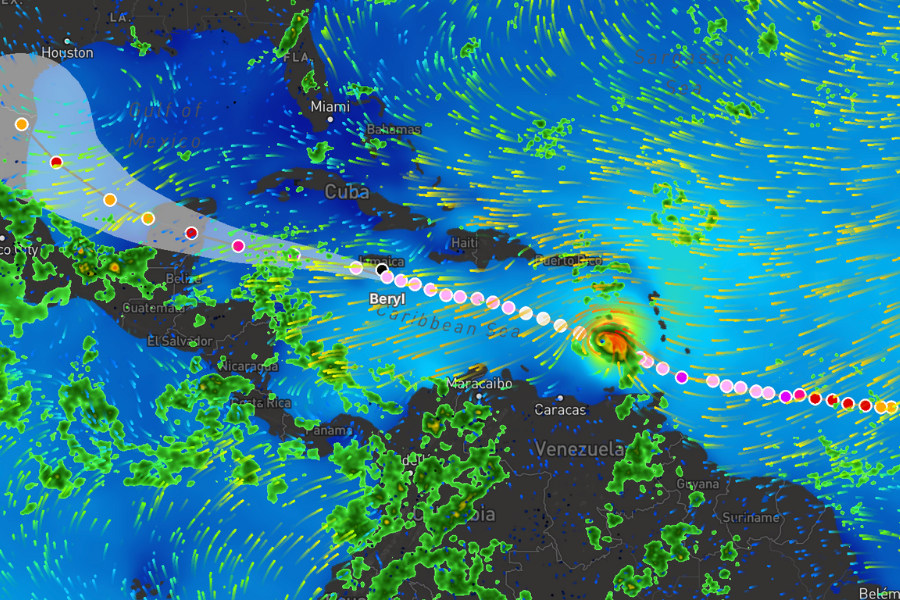

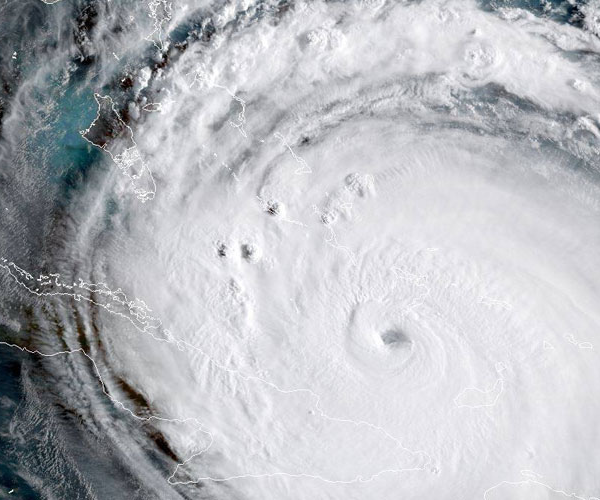

Monitoring technology like our satellites is improving rapidly. Compare the first television picture of earth from space, taken by TIROS-1 in 1960, to recent satellite imagery of Beryl’s eye in the recent satellite images from July 2024. (Credit: TIROS Program, NASA; CSU/CIRA & NOAA.

Not now means not yet

While we might not see an increase in the number of hurricanes now, it doesn’t mean change isn’t coming.

With limited historical hurricane data, it is a challenge to differentiate storm trends driven by climate change from the natural variability of these storms. What we do know is that sea surface temperatures are warming, which has a direct impact on storm development. Since 1971, there has been an increase in the rate of rapid intensification* of cyclones in the Atlantic. Warmer surface temperatures are also expected to increase extreme rainfall events during tropical cyclones.

*Rapid intensification, or RI, is basically what it sounds like – the name for when a tropical cyclone strengthens quickly over a short period of time.

As populations grow and development spreads to vulnerable areas, we must adapt our approach to preparing for, monitoring, and protecting against disasters.

“... even if the severity of natural hazards remains constant, the potential impacts of those hazards are likely to be amplified as population increases along coastal areas and demographic composition shifts towards more vulnerable groups.”

The changing demography of hurricane at‐risk areas in the United States (1970–2018), Park, 2023